How I Structure My Data Pipelines: The Bronze Layer

The goal is for data to be as boring and predictable as possible

Introduction

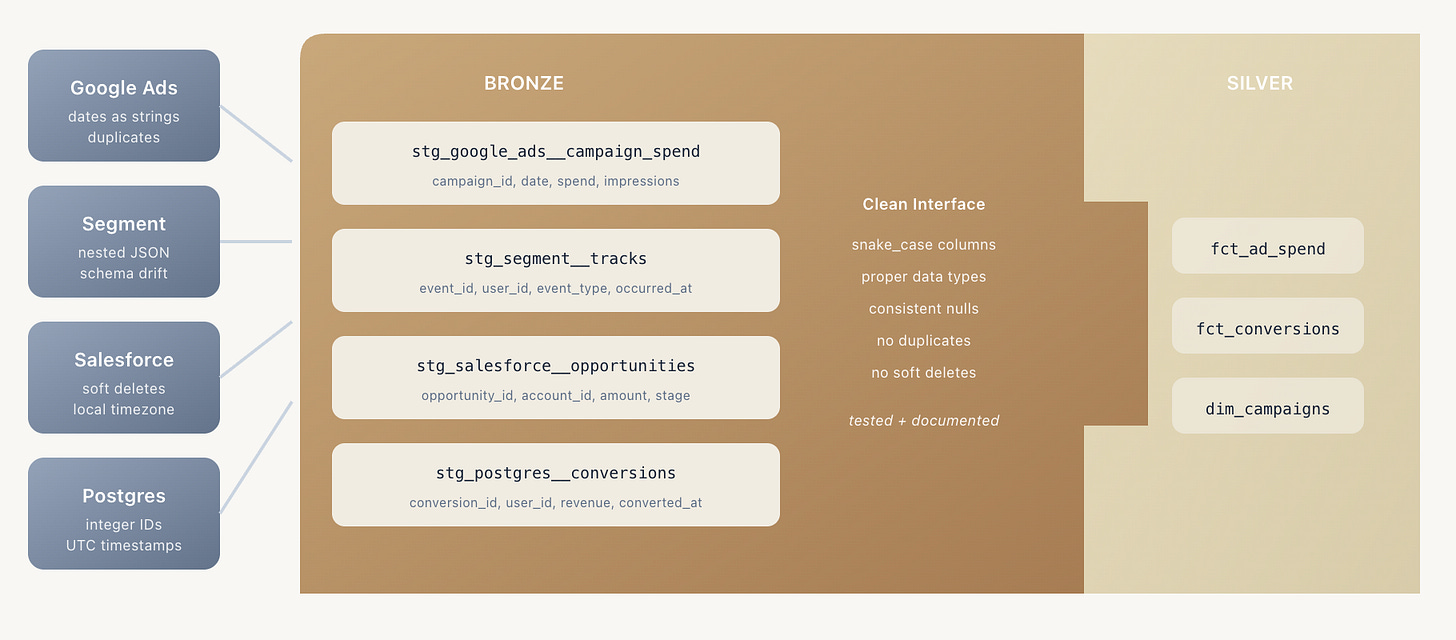

In a previous post, I laid out how medallion architecture, dimensional modeling, and semantic layers fit together into a single coherent approach. Each layer produces its own artifacts, serves its own consumers, and solves its own problems.

The next three posts go deep on each layer. This one covers Bronze, including naming conventions and its role as an interface for Silver.

But first: Bronze. Some literature treats it as a landing zone for raw source data, a place where data arrives untouched before any transformation happens. My Bronze is different. Some of my power users in the business need to be able to look at source-level data to analyze individual records, which means the data needs to be refined and standardized enough to actually work with. Bronze is where I make raw data predictable and boring.

Think of building the bronze layer as if you’re doing prep work ahead of a

And if you’re neurotic like me, you need all of the little pieces to be straightened and all the wrinkles ironed out before ever actually trying to put any deep work into it.

Doing this prep work means everything is organized and ready to use before the real modeling begins in Silver. You’re not constantly context-switching back to source quirks while trying to think about business logic.

This is my version, the approach that’s worked well for me. I’m not claiming it’s the only way or the best way. I’m just sharing what I’ve landed on after iterating through a few different approaches.

A note on tooling: the examples here use dbt, but the patterns matter more than the technology. Tests, documentation, contracts, and naming conventions are ideas that translate to any framework. If you’re using SQLMesh or raw Spark, the patterns and concepts of writing tests, documents, et al still apply.

The Mess

Before modeling the business, the sources need to be wrangled. And sources are messy.

Every source has its quirks, and those quirks are rarely documented:

Ad platform exports include soft-deleted records by default, so every downstream query needs a WHERE clause to filter them out. Someone on the team figured this out three years ago, but they never wrote it down.

Clickstream data arrives as nested JSON. The schema evolved twice last quarter, and events before March 2023 are missing a field entirely due to a bug that was never backfilled.

This is tribal knowledge. It lives in Slack threads and in the memories of people who got burned by it once. It hides in code comments that say “don’t remove this filter” without explaining why.

A new analyst joins the team and builds a report. They don’t know about the soft deletes, so the numbers are wrong for three weeks before anyone notices. Then they learn. And someday they’ll leave, and someone new will make the same mistake. Generational trauma, data team edition.

Bronze exists to break that cycle. The job is to make raw data predictable and boring.

Predictable means people can make assumptions. A column named campaign_id contains campaign IDs. A primary key is unique. Company names are normalized, so you don’t have to wonder whether the source stored it as “ACME Corp” or “acme corp” or “Acme CORP.” Predictability means fewer surprises, fewer wrong reports, and less time debugging.

What Bronze Does

Bronze normalizes and standardizes source data into something predictable. The goal is to do just enough to make the data safe and reasonable to query, without adding any business logic.

All the work here involves simple operations: column renaming, type casting, and basic filtering. No complex joins or aggregations. The output is a clean, boring representation of each source. Not interpreted or modeled, just normalized into predictable patterns. A business user who needs to audit source records or investigate why a specific account behaves unexpectedly can query Bronze directly without needing to remember all the tribal knowledge. It’s already been handled.

What Belongs in Bronze

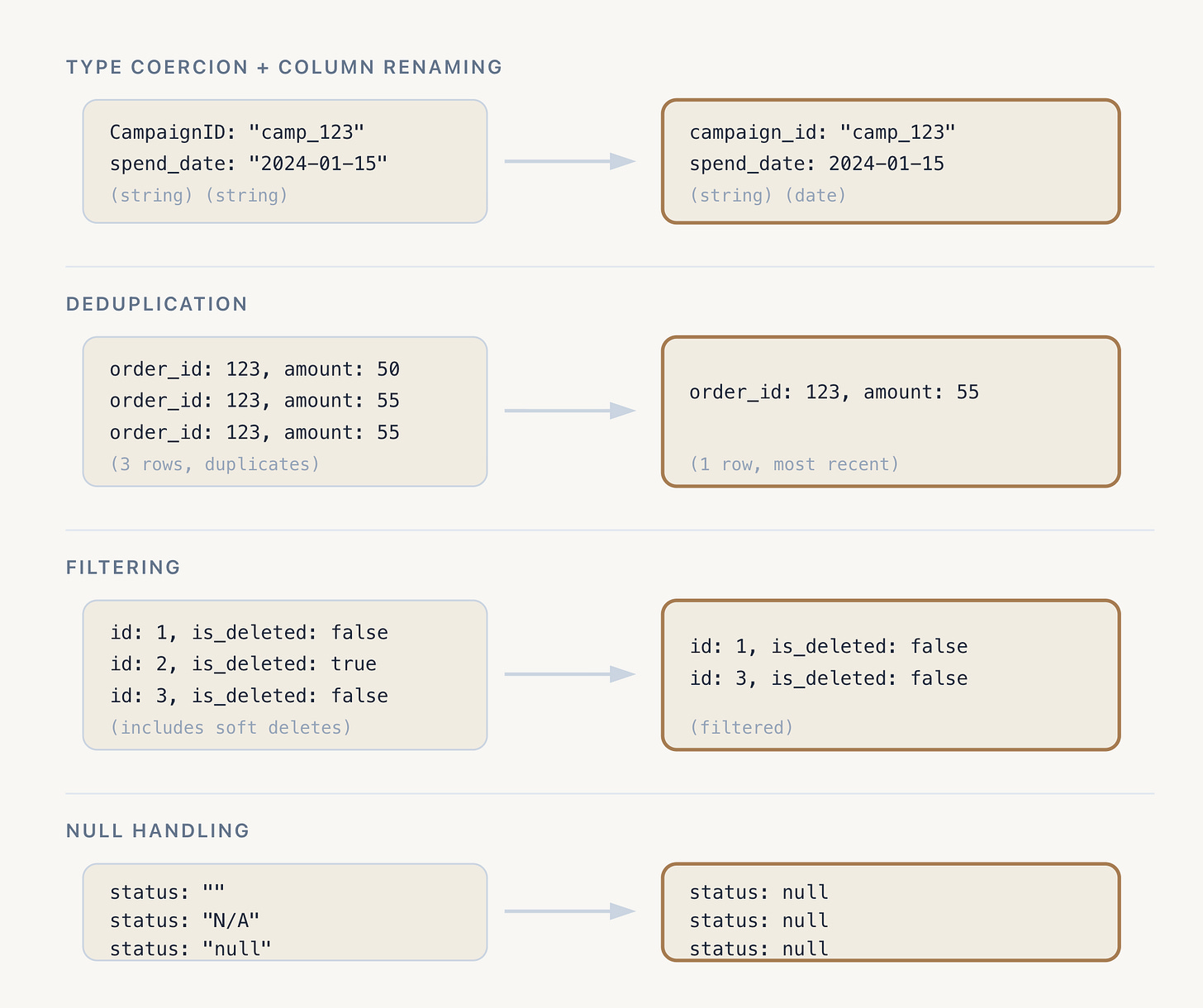

The work is mechanical and fairly rote: make source data consistent and queryable without interpreting it. These are prime candidates for an agent to transform, then have the developer go back and refine afterwards.

Source systems have their own conventions, and we standardize to our team’s type and naming standards here. Date strings are cast to the appropriate date types. Numeric strings become numbers. The goal is a consistent schema that downstream models can predictably rely on.

Some sources deliver duplicate records, especially event streams and CDC pipelines. I handle that by taking the most recent version of each record based on a timestamp or sequence number.

Sometimes, preserving duplicate records downstream is important. If so, then we don’t dedupe. However, in my experience, that’s been the exception and not the rule.

Filter out records that shouldn’t be there, such as soft deletes, test accounts, and records before a known data quality cutoff date.

Light denormalization within a single source. Nested JSON gets unpacked into flat columns. Arrays might get exploded into rows.

Different sources represent missing data differently: empty strings, “N/A” values, string literals like “null”, or the number zero when it should be null. Normalize all of these to consistent nulls.

Inputs Vary

Bronze is often described as the “raw data” layer, which implies CSVs, API dumps, and database extracts. The wide variety of heterogeneous data sources is the most difficult part of designing a bronze layer.

There’s one type of input data that people take for granted and catches people flat-footed: sometimes the input is another team’s modeled output, such as their facts and dims. In organizations with multiple data teams, it’s common to receive data that’s already been cleaned and modeled by someone else.

I still run this through Bronze. It’s where I establish my contract, apply my naming conventions, add my tests, and conform to my domain’s expectations. Whether the input is a raw export or a polished table from another domain, this is where I prepare it for my pipeline. The pattern holds regardless of how refined the input already is.

Implementation Details

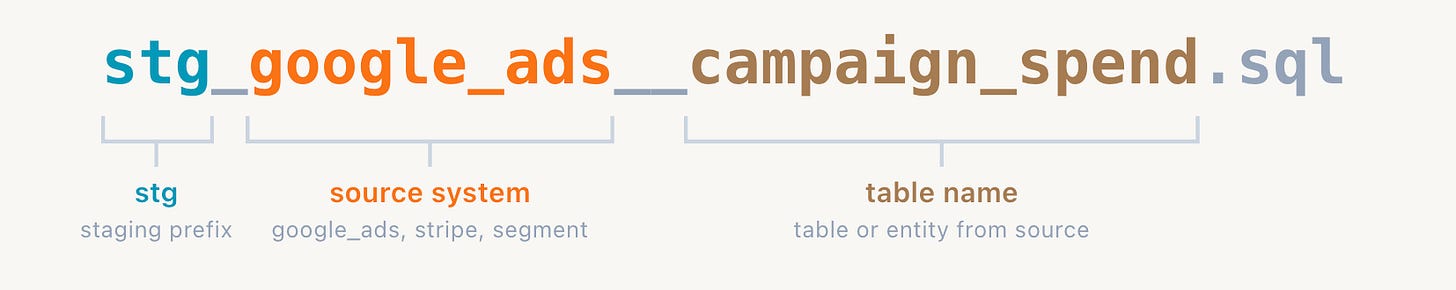

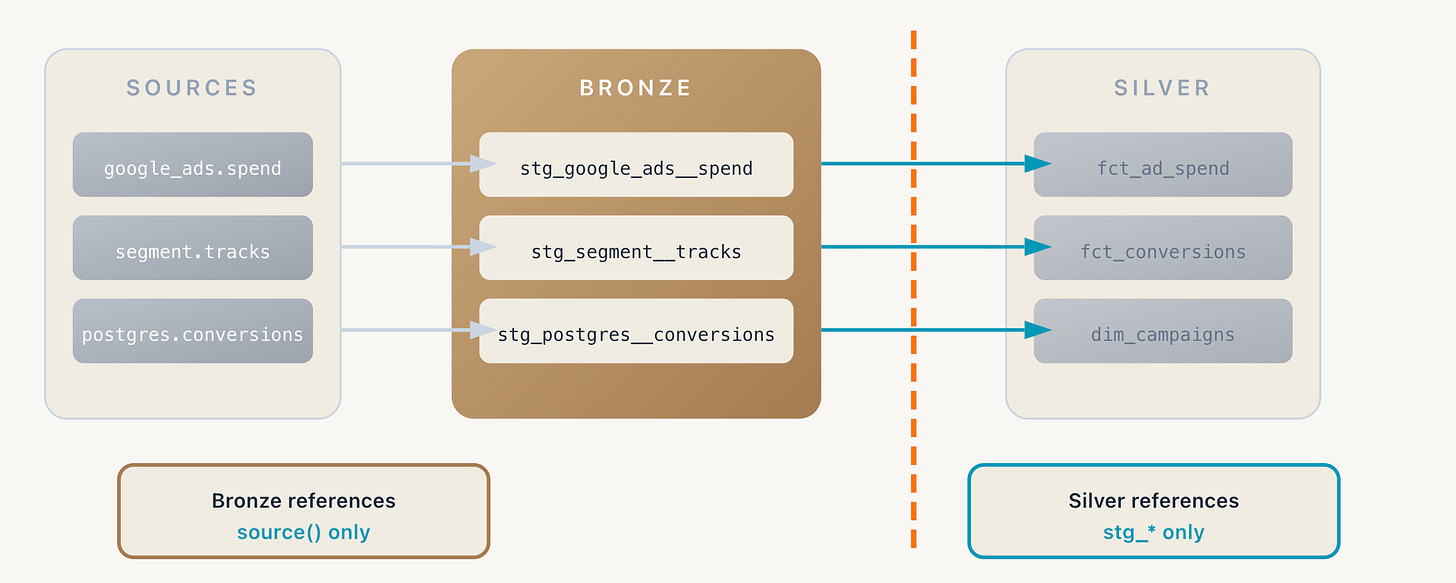

Naming convention: I follow the pattern stg_{source}__{table}.sql. When you see stg_google_ads__campaign_spend, you immediately know the source system (Google Ads) and the specific table (campaign spend). This matters when you have dozens of staging models and need to find the right one quickly.

The stg_ prefix signals that this is a staging model, which tells anyone reading the code what layer they’re in. Consistency here pays off when someone new joins the team. They don’t have to learn your naming scheme from scratch because the pattern is self-documenting.

Materialization: Views. The transformations are simple enough to run at query time, so there’s no need to persist the results. This keeps storage costs down and means the data always reflects the current state of the source. When the source table is updated, the view automatically contains the new data. No orchestration required.

Schemas and environments: Production and development live in entirely separate catalogs and workspaces. This separation is fundamental to how the whole system operates.

In production, schemas follow the pattern bronze_{source}. The schema name makes it immediately clear what layer a model belongs to. When someone sees a table in bronze_google_ads, they know it’s a staging model from the Google Ads source without having to look at the code. Production schemas are read-only for most users. Only the orchestration service account can write to them, and changes only happen through the CI/CD pipeline. This means when you query production, you’re getting the blessed, tested, reviewed version of the data.

Development is a different world. Within the dev database, each engineer gets their own schema, typically named after their username. When you run a build in development, your models materialize in your personal schema. You can drop tables, rebuild from scratch, and experiment freely without affecting anyone else.

But isolation isn’t the whole story. Everyone on the team should have read access to each other’s dev schemas. This matters more than it might seem:

When someone pings you about a weird data issue they’re seeing, you can query their dev models directly instead of waiting for them to share screenshots or push their code.

When you’re pairing on a problem, both people can run queries against the same dev schema and compare results.

When someone’s out sick and their work needs to be picked up, the team can see exactly where they left off.

The catalog separation also helps with cost management. Dev workspaces can have lower compute limits and shorter auto-suspend timeouts. You don’t need production-grade performance for development work, and you definitely don’t want a runaway dev query burning through your compute budget.

Dependencies: Staging models reference only source data. In dbt terms, they use source() and never ref(). This constraint keeps Bronze focused on its job: normalizing source data. If you find yourself wanting to join two staging models together or reference another staging model’s output, that logic likely belongs in Silver.

The spec file: Each source gets a _{source}__bronze.yml file that lives alongside its staging models. This is where the contract lives: model descriptions, column descriptions, data types, and tests.

Here’s what one might look like:

models:

- name: stg_google_ads__campaign_spend

description: Daily spend by campaign from Google Ads exports.

columns:

- name: stg_google_ads__campaign_spend_id

description: Surrogate key for this staging model.

data_type: string

tests:

- unique

- not_null

- name: campaign_id

description: Unique identifier for the campaign.

data_type: string

tests:

- not_null

- name: campaign_name

description: Display name of the campaign.

data_type: string

- name: spend_date

description: The date the spend occurred.

data_type: date

tests:

- not_null

- name: spend_amount

description: Total spend in USD.

data_type: decimal(10,2)

tests:

- not_null

- dbt_utils.accepted_range:

min_value: 0

- name: channel

description: Marketing channel.

data_type: string

tests:

- accepted_values:

values: ['search', 'display', 'video', 'shopping']

The spec file serves two purposes. First, it documents what the staging model produces. Column descriptions explain what each field contains, and the data types make the schema explicit. Second, it encodes testable assertions. The surrogate key stg_google_ads__campaign_spend_id is generated from the combination of campaign_id and spend_date, and the unique and not_null tests on it tell downstream models they can treat it as a proper primary key. The accepted_values test on channel tells them exactly which values to expect. The accepted_range test on spend_amount confirms it’s never negative.

If a column isn’t described in the spec file, Silver shouldn’t depend on it. The spec is the contract. Everything outside of it is an implementation detail that might change.

Bronze as an Interface

Each staging model is a contract that Silver consumes. But the contract isn’t just about catching problems. It’s about encoding assumptions so nobody has to rediscover them.

Without this, every person who touches a source table has to build their own understanding of it. They run exploratory queries to answer basic questions:

What’s the grain of this table?

Which column is the actual primary key?

What values appear in the status field?

Which columns can be null?

They build intuition through trial and error, and eventually feel confident enough to use the data. Then another analyst comes along and repeats the same work. The exploratory effort compounds because nobody wrote down what they learned.

Bronze is where you do that work once and make it available to everyone. You define the primary key and test that it’s unique, list the accepted values for enums, document the expected ranges for continuous values, and note which columns can be null. These aren’t just validation checks. They’re assertions about the data’s shape that others can rely on.

When someone opens the catalog and looks at a staging model, they should be able to understand the data without running a single query. The tests and documentation answer the questions they would have asked. A uniqueness test on event_id tells you it’s a primary key. An accepted_values test on channel tells you the exact set of values to expect. A not_null test tells you the column is safe to use in joins. The more assumptions people can safely make, the faster they can move.

This also shifts left as hard as possible. When a source changes, a test fails before Silver breaks. And when tests fail with warnings instead of errors, that’s useful too. A warning means this assumption doesn’t hold, so don’t rely on it. You’re learning about your data’s actual shape, not just whether it matches your expectations.

Example: Marketing Attribution

Three sources feed an attribution model.

Google Ads delivers spend by campaign as daily CSV dumps. The dates arrive as strings in inconsistent formats, campaign names have trailing whitespace, and some days have duplicate rows.

Segment sends clickstream events as nested JSON. Timestamps are in UTC, but the schema isn’t always consistent across event types.

An app’s Postgres backend contains conversion events from the application database. The column names follow the backend’s naming conventions, which don’t match the data team’s naming conventions. IDs are integers in the source but need to be strings in the warehouse for consistency with other systems.

The staging models handle these quirks:

stg_google_ads__campaign_spendnormalizes the CSV export by casting date strings to dates, trimming campaign names, and deduplicating on campaign plus date.stg_segment__tracksunpacks the nested event payload, casts timestamps to proper timestamp types, and normalizes null handling across event types.stg_postgres__conversionsrenames columns from the backend’s conventions, casts IDs to strings, and handles timezone conversion.

Silver doesn’t need to know that Google Ads has inconsistent date formats or that Segment events arrive as nested JSON. Bronze has already handled that.

The interface between Bronze and Silver is clean. Silver models reference staging models by name and trust that the contracts are enforced.

What’s Next

Post 3 covers Silver, the dimensional modeling layer. I’ll walk through facts, dimensions, grain, conformance, and my rendition of the “intermediate” models for shared transformations.

Please ignore my prior post about bronze - you explain it here.

I'm unclear about the views part - are you saying that bronze is only made up of views connected to source data in another system, OR that its made up of raw data, and then cleaned up by views, or something else?