How I Structure My Data Pipelines

Making sense of ~5 years of vendor speak, 10 different architectures that are actually the same, semantic layers finally maturing, and a Bartridge in a B-tree.

The medallion architecture is everywhere. If you’ve worked with a modern data platform, you’ve probably encountered some version of it. Databricks popularized the Bronze/Silver/Gold naming, but the pattern has many aliases. dbt talks about staging, intermediate, and marts. Other teams use raw/curated/refined, or landing/transform/serve. The branding differs, but the core idea is the same: data flows through layers of refinement, from source to consumption.

The appeal is that it gives you a simple mental model for organizing a data project. You always know roughly where to look for something. The problem is that the layer definitions are loose enough to mean different things to different people. What counts as “cleaned”? A data engineer might mean clean facts and dimensions. An analyst might mean “ready to query without thinking about joins.” Two teams can both claim to follow medallion architecture and have completely different ideas about what belongs in Silver.

This post shares how I’ve come to structure it. My approach combines medallion, Kimball dimensional modeling, and semantic layers into a single architecture. Each pattern solves a different problem, and when you map them onto the three layers intentionally, you get something that’s both principled and practical.

For readers that want a canon definition of the medallion architecture, Databricks’ documentation provides a clear overview. The rest of this post assumes basic familiarity with the concept.

Medallion, Kimball, Semantic: A Quick Tour

When people talk about data architecture, three patterns come up repeatedly. Each one solves a real problem, and each has a body of literature behind it.

The Medallion architecture is a structural pattern for organizing a data project. Data moves through layers of progressive refinement. It’s a way to answer “where does this model live?”, but it doesn’t prescribe what each layer should contain. Databricks popularized this pattern with their lakehouse architecture, and it’s become a common default for teams building on modern data platforms.

Kimball gives you a methodology for modeling business data. Facts capture measurable events at a declared grain. Dimensions provide descriptive context. Conformed dimensions resolve the same entity across sources. It’s a way to represent the business accurately, but it doesn’t tell you how to organize your project. The methodology comes from Ralph Kimball’s work on dimensional modeling, and Joe Reis covers the practical application well in Practical Data Modeling.

A Semantic Layer provides a consumption pattern for governed metrics, self-service access, and abstraction over physical tables. It’s a way to expose data to end users in the form of pre-defined measures and dimensions.

These patterns answer different questions. Medallion is about project structure. Kimball is about data modeling. The semantic layer is about consumption. They’re complementary, and the interesting question is how to combine them.

How I Combine Them

Once I saw these as answering different questions, the mapping became straightforward.

Bronze is staging. Sources land here. The work is mechanical: normalize column names, cast types, deduplicate, handle nulls, and don’t apply business interpretation. The output is a clean, consistent representation of what each source system provided.

Silver is where Kimball belongs. This is where you model the business. Facts capture measurable events at a declared grain. Dimensions provide the descriptive context for slicing and filtering. Slowly changing dimensions track historical state. Conformed dimensions resolve the same entity across multiple sources. The output is an authoritative dimensional model that represents how the business actually works.

Gold is the semantic layer, in my case, powered by Databricks Metric Views. Metric views define calculations once and provide a centralized place to define measures, dimensions, qualitative metadata, and business context directly within a database object. Governed definitions mean “revenue” is the same number in every dashboard. The output is a self-service interface that analysts and tools can query without writing SQL or understanding joins.

Each Layer Serves Different Consumers

The architecture doesn’t funnel everyone through Gold. Each layer has its own audience, and they’re often different people with different needs.

Gold is where most analytical work happens. Analysts building dashboards connect here. Business users run self-service exploration queries here. AI tools pull governed metrics from here. The common thread is that these consumers want pre-defined metrics and dimensions. They don’t want to write SQL or figure out how tables join together.

Silver serves people who need more flexibility than Gold provides. An analyst exploring a question that hasn’t been modeled yet might query Silver directly. A data scientist building features for a model needs access to the whole grain of the dimensional tables. These consumers are comfortable with SQL and need to work with the data at a level of detail that governed metrics don’t expose.

Bronze serves people who care about individual source records. A data engineer debugging a quality issue might trace a record back to Bronze to see exactly what arrived from the source system. An analyst auditing a specific transaction needs to see the original values before any transformation. These are typically investigative use cases, and Bronze gives you the rawest view available.

Making the Semantic Layer a First-Class Priority

The semantic layer used to be an afterthought. People would finish their dimensional model, hand it off to someone else to make OLAP cubes, or define their own metric definitions in whatever tool they used.

That’s changed in the last year or so as semantic layer tooling has matured significantly. Databricks shipped Metric Views. Snowflake introduced semantic view objects. These tools share a common idea: defining metrics as first-class database objects rather than leaving them embedded in dashboard SQL or spreadsheet formulas.

A metric view defines dimensions (the attributes users group by and filter on), measures (calculations, such as summing revenue or computing cost per acquisition), and hierarchies (drill paths, such as year-to-quarter-to-month-to-day). BI tools query the metric view directly, and the definitions are centralized in one place rather than reimplemented in every dashboard.

Building a proper consumption layer used to mean maintaining custom aggregation tables by hand or relying on semantic layers built into specific BI tools, which locked you into that vendor. Now it’s a database object.

The barrier has dropped enough that there’s no reason to treat the semantic layer as something that happens after modeling. It can be built directly into your pipeline, with the same rigor you’d apply to your facts and dimensions. That’s why I’ve given it a dedicated spot as the Gold layer.

OBTs and Dimensional Models Work Together

There’s a common framing in data modeling discussions that treats dimensional models and OBTs as either/or choices. You build facts and dimensions with proper star schemas, or you build one big table with everything pre-joined. In practice, you can do both.

The OBT is a consumption artifact. It belongs downstream of your facts and dims.

Silver is where you do the dimensional modeling work. As mentioned, the Silver layer holds the facts at declared grains, dimensions with proper keys, conformed entities, and historical tracking.

Gold is where data is surfaced in easy-to-consume ways. Sometimes that’s a metric view with governed definitions. Sometimes that’s a wide table that pre-joins the relevant facts and dimensions so users don’t have to think about the joins themselves.

You get the rigor of dimensional modeling and the usability of wide tables. One feeds the other.

A Concrete Example: Marketing Attribution

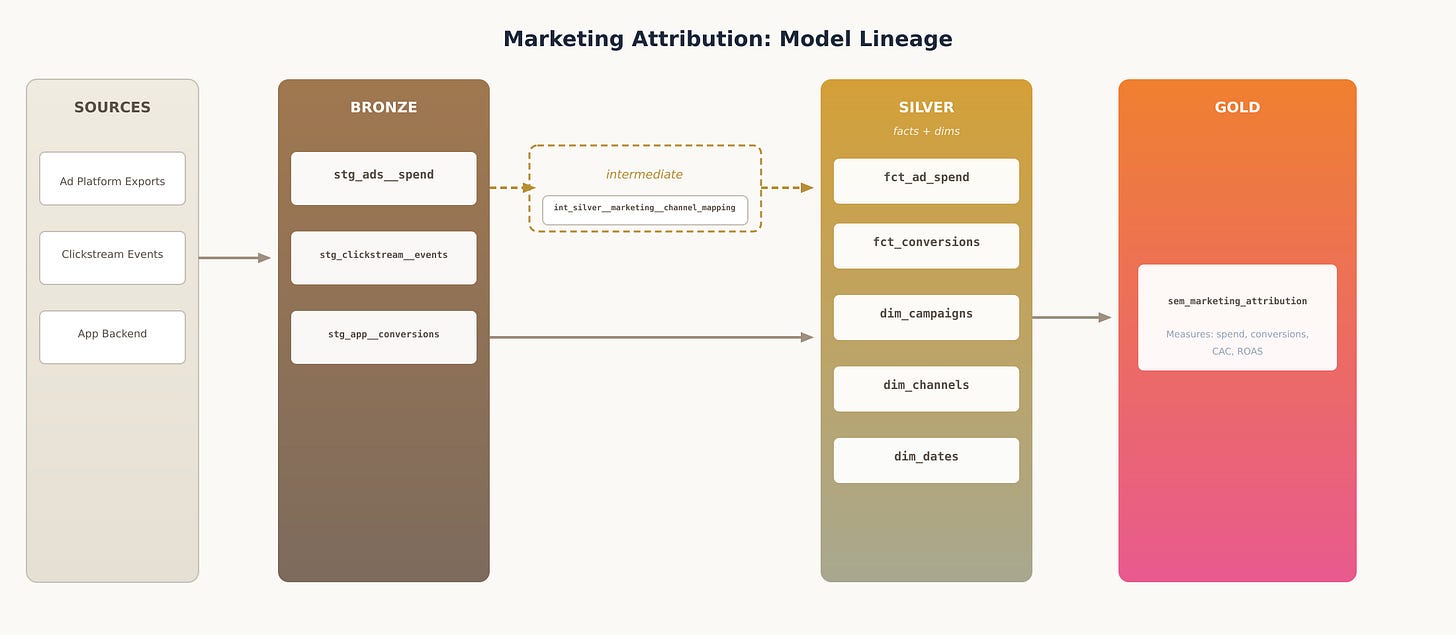

To make this tangible, here’s how marketing attribution data flows through the architecture.

Bronze receives data from three sources: ad platform exports with spend by campaign, clickstream events from web analytics, and conversion events from the app backend. Each source lands in its own staging model. The work here is mechanical. Cast the date strings to proper dates. Normalize the column names. Deduplicate records. Handle the timezone differences between systems. No business logic, just clean representations of what each source provided.

An intermediate model consolidates the inconsistent channel naming conventions across ad platforms into a single taxonomy. This shared transformation feeds both the channel dimension and the ad spend fact. Intermediates like this are internal plumbing. They exist to serve the models that get documented and tested.

Silver is where the business model takes shape. A campaign dimension consolidates campaigns across all three ad platforms into a single conformed entity. Fact tables capture ad spend at the campaign/channel/day grain and conversions at the event grain. This is the authoritative representation. When someone asks, “What’s a campaign?” the Silver dimension is the answer.

Gold surfaces these models for consumption. A metric view defines the measures that matter: total spend, total conversions, cost per acquisition, and return on ad spend. Analysts query the metric view directly. They pick dimensions and measures without writing SQL. The CAC calculation is defined once, and every dashboard that uses it gets the same number.

Closing

If I remember, there will be other posts. Posts further into this series will use this example throughout, showing the model structure, naming conventions, and implementation details at each layer.

That is a good post, thanks for the good context especially for people new to subject. Layers in a model are important, but no religion. I worked on setups where we skipped staging completely because it felt redundant. I really like your definitions what each layer does. This is essential for me to have these in place (even better extended in a doc). Because you can then let Claude Code check your staging models for any violations (there is business logic).

The difference in my models is that I use activity models instead of fact (because more of them and more granular) and my attribution setup is a bit more extended to support virtual touchpoints and rule-based attribution (but I guess you skipped that for the sake of simplicity of the visual).

I'd find this confusing as everything you are doing in your bronze layer (deduplication, normalisation etc) happens in the silver layer in a classic medallion architecture, and is well explained in the databricks link you included.